Raising the Roof

By Michael Bridgeman

For a design that was born in 16th century France, the mansard roof has had remarkable staying power. In its 400-year history the distinctive roof has adorned everything from grand French chateaux to Gilded Age hotels and American fast-food restaurants.

Origins

The mansard roof first appeared in Paris in the 16th century and was popularized in the 17th century by Francois Mansart. Though he was reportedly difficult to work with, that didn’t stop the richest and most influential aristocrats from engaging his services. Mansart is credited with bringing classicism to high-style Baroque architecture in France, though he also had a penchant for the emphatically non-classical roof that has come to bear his name.

Exuberant mansard roofs top the Château de Maisons-Laffitte, a glorious country house near Paris designed by Francois Mansart and competed in 1651.

The mansard re-emerged in France two hundred years later during the regime of Napoleon III, with the expansion of the Louvre. When Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann was engaged to remake Paris, his building program mandated mansard roofs, many of which still rise above the boulevards. Napoleon III’s reign (1852-1870) was known as the Second Empire and that name stuck when the French style was imported to the United States.

Second Empire in America

The Second Empire style and its mansard roof was very much á la mode in the United States during the 1860s and 1870s. Paris was becoming the cultural capital of Europe, so it’s not surprising that American designers and consumers were smitten by the French style. Second Empire buildings were popular from coast to coast for buildings large and small and Madison had its share of mansard-topped structures. The largest and grandest, including the old post office and the original Park Hotel, are long gone.

When the Park Hotel opened in 1871 it had an imposing and very fashionable mansard roof. The Second Empire design by Stephen Vaughan Shipman endured until shortly before World War I. The hotel has been expanded and refashioned several times since.

Image: Undated postcard; author’s collection

As Barbara Wyatt notes in her 1986 manual for historic properties in Wisconsin:

Historic photographs and lithographs suggest that Second Empire buildings were once more common in Wisconsin than the contemporary inventory might indicate. The style was popularly utilized for large public and institutional structures, but the attrition rate has been high, as they were replaced by "modern" buildings in the late nineteenth century.[1]

Residential architecture is where we see Madison survivors of the first flowering of American mansards. The unmistakable feature of the Second Empire style is the mansard roof with its two slopes on all four sides. The upper slope may be very shallow or even flat and the lower, more steeply angled slope may have a straight, concave or convex profile. Dormer windows, which came in a variety of shapes, were nearly universal and provided light and air for the living space contained by mansards.

Madison’s rapid growth in the 1850s predated the arrival of the Second Empire style in the U.S. That didn’t stop the big bugs of Mansion Hill from embracing the style when they remodeled their already-grand houses after the Civil War. Adopting the French style was a clear demonstration of their up-to-date taste and good judgment. Not incidentally, remodeling also gave them more living space.

Madison’s most spectacular extant example of a mansard roof is the George Keenan House [2] at 28 E. Gilman St. (1857/1870). August Kutzbock designed the massive brick house circa 1858 in the Germanic “round arch style.” From bird’s-eye views we know the house acquired its glorious new mansard roof sometime before 1885.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

The Italianate and Second Empire styles co-existed. Wyatt notes that while the design movements were independent of each other, “elements of Second Empire influence can be found in some Italianate houses.” It was relatively easy to “modernize” an Italianate house with a mansard roof and create a pleasing result.

The John Kendall House at 104 E. Gilman St. (1855/1873) started its life as an Italianate building. Less than than twenty years later it was transformed with a mansard roof which had an uncommon S-curve to its lower slope. This photo from 1931 shows decorative cresting along the roof line and front porch, which have not survived.

Photos: Wisconsin Historical Society Image ID 36698

Mansard roofs did not only appear on big, fancy houses. Madison has several “cottages” that are made grander by having Second Empire style roofs. The ones I’ve spotted are downtown or on the near east side. In large, cosmopolitan cities the Second Empire fad had peaked by the mid-1880s, but some examples continued to be built in smaller communities like Madison for another decade or so.

This small house near Orton Park aspires to high style. The P.G. Krogh House at 1120 Jenifer St. (1887) has second-story windows cut into the steep slope of the mansard roof rather than projecting as dormers, a choice that may have saved on building costs.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

After fading from the scene, mansard roofs were not often used on new construction for nearly a century. A notable local exception was designed by Madison architect Frank Riley for Kessenich’s Department Store. Skilled at adapting historical revival styles to modern uses, Riley turned to the French Renaissance for the fashionable women’s clothing store on State Street. His design is refined and understated, unlike the more imposing structures of the 19th century Second Empire style.

The original design for Kessenich’s Department Store (1923) at 201 State St. had a single steep slope to it mansard roof. The upper tier of the mansard was added in 2001 when the façade was integrated into the new Overture Center.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

Modern Mansards

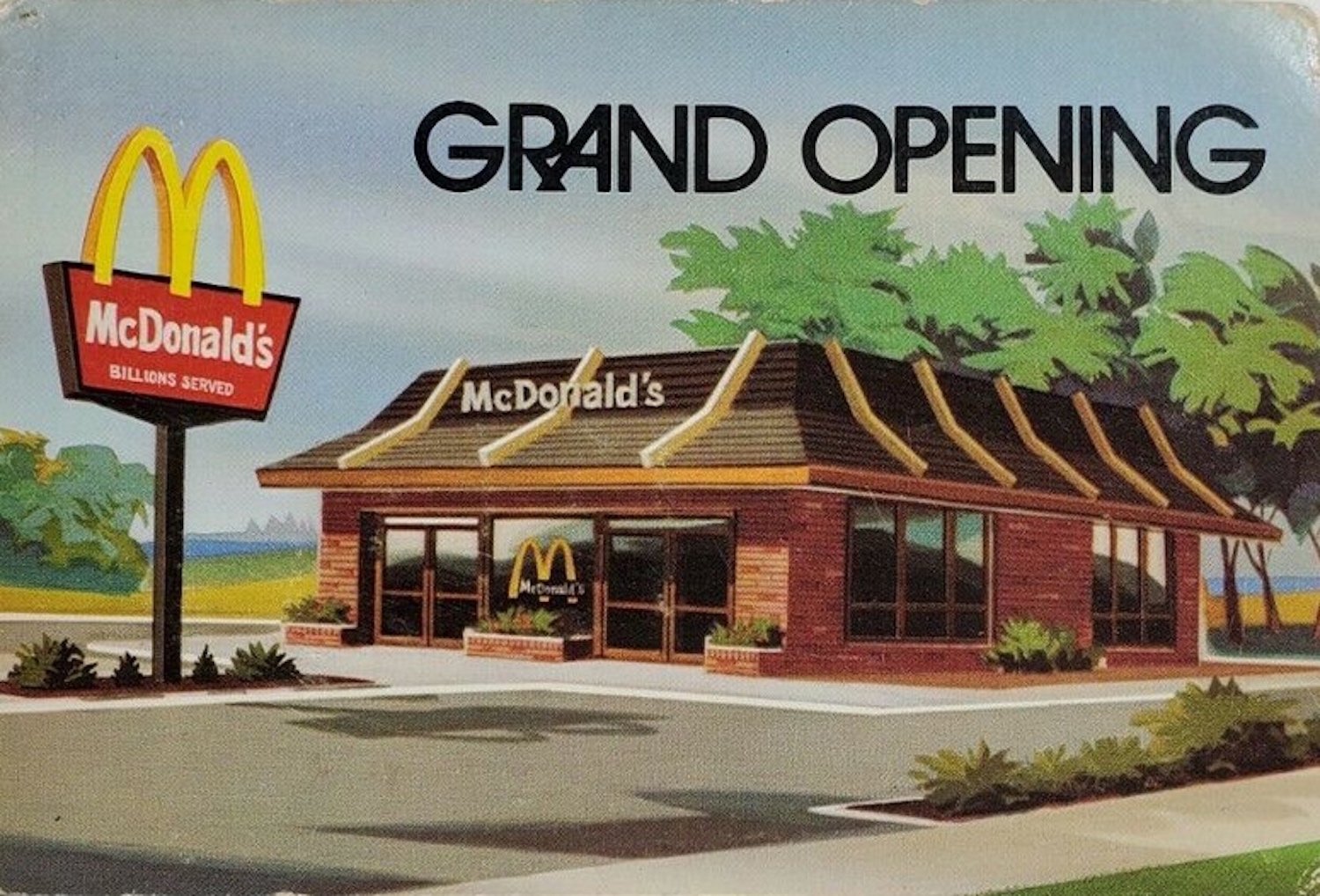

In the late 1960s the mansard roof made a comeback, spurred in part by fast food restaurants. As buildings erected by McDonalds and its competitors multiplied they were increasingly seen as a blight on towns and cities. In 1969 McDonald’s introduced a new restaurant design in a Chicago suburb that featured a “double mansard,” as the company’s chief architect called it.[3]

An illustration of McDonald’s new design appears on a postcard from 1971 announcing the grand opening of a restaurant in the Chicago area. The “double mansard” roof influenced roadside architecture for several decades.

Image: Postcard, author’s collection

The new McDonald’s design inverted the usual mansard profile: the lower slope was shallow and the upper slope was steep. Its development was driven, in part, by the need to screen unsightly roof-top mechanicals which could now hide behind the upper part of the roof. The material choices (asphalt shingles and brick) and subdued colors (brown and beige) also helped to mollify critics who decried the blaring oranges, yellows and reds of many fast-food outlets.

“The ‘mansard’ was the least expensive means of displaying a somewhat traditional roof, yet creating plenty of space out-of-doors [on rooftops] for restaurant equipment,[4]” according to Philip Langdon. McDonald’s patented their roof configuration to discourage duplication. But competitors were under the same pressures to reduce “visual pollution,” so Burger King, Dunkin’ Donuts, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and others moved in similar directions when updating their store designs.

A mansard-like roof with a concave profile survives on the Wendy’s restaurant (1980/1985) at 3910 E. Washington Ave. The exhaust vent visible on the left is the only equipment not screened by the roofline.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

At about the same time gas stations, not-so-distant cousins to fast food restaurants, were also pushed to improve the look of their numerous locations in cities, suburbs and small towns. Company architects were not immune to the latest commercial style. “False, shingle-clad mansard roofs, which topped most station makeovers, became an aesthetic cliché of the late 1960s and early 1970s,”[5] writes Jim Draeger in his book about Wisconsin gas stations.

A former gas station at 3415 Parmenter St. in Middleton combines a shingled mansard roof with gables over the service bay doors.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

These roadside buildings use quasi-mansards[6], not true mansard roofs. They lack the usual double-pitch silhouette, typically displaying only the steep slope of the “roof,” which was cheap to build and could conveniently accommodate store signage. Quasi-mansards don’t enclose habitable space so never include dormer windows. Still, there are commercial buildings from the 1970s and 1980s that acknowledge the precedents established in the 19th century, though in stripped-down versions typical of most modern takes on historic styles.

This small office building at 216 N. Midvale Boulevard (1959) was remodeled in 1972, which is when the mansard roof was probably added. Here the style connects more directly to the Second Empire style of 100 years earlier: the straight roof silhouette flares at the lower eave, the roof encloses useable space, and the dormers are topped with segmental arches.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

Modern single-family homes with mansard roofs are not common, though I usually encounter a few among the contemporary, colonial revival, and “half-timbered” houses in residential areas developed in the 1970s. Some of these houses take their French pedigree fairly seriously while others play with the mansard form and contemporize it, with varying degrees of success.

While the house at 5318 Comanche Way (1972) is clearly modern, it employs enough traditional touches—including segmental arched window and door openings, and brick quoins at the corners of the facade—to make the mansard roof part of a credible and cohesive composition.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

The shingled roof at 318 North Yellowstone Drive (1970) stretches the mansard tradition by framing the second-story windows inside deep segmental arches plus one square arch. The multi-colored brick and board-and-batten siding connect the house to mid-century design trends.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

Mansard roofs in a variety of forms and materials often appeared 30 to 50 years ago on multi-family buildings and are easy to spot all across the Madison area. Their purpose is decorative, a way to add a touch of “style” or “distinction” to what are, most often, fairly routine projects, many with multiple buildings set among surface parking lots. Quasi-mansards have even appeared atop apartment buildings of relatively recent vintage.

The double pitch of a traditional mansard roof is evident on this multi-unit building, now condominiums, at 602 North Westfield Road (1974). The second-story windows are cut into the steep slope as at the 1887 Krogh House above.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

A dramatic two-story, copper-clad mansard roof tops the Aberdeen Apartments (2004), a 77-unit building at 437 W. Gorham St. in downtown Madison. This is one of several 21st century projects to sport the centuries-old form.

Photo: Michael Bridgeman

I now notice mansards and, more often, quasi-mansards pretty much any time I take a walk or drive. Some are impressive while many disappoint. Some evoke smiles and others induce winces. In any case, I find the continued use of the mansard roof endlessly interesting.

___

[1] Barbara Wyatt, Cultural resource management in Wisconsin: a manual for historic properties (Madison, Wis: Historic Preservation Division, State Historical Society of Wisconsin), 1986. Vol. 2, Architecture 2-11

[2] This house is sometimes referred to by other names. The house was built for Napoleon Bonaparte and Laura Van Slyke. Laura died and it is said that N.B. never lived in the house. The first resident owners were Ellen and James Richardson. He was a close friend of Van Slyke, a real estate speculator and banker. George Keenan’s name appears in the 1890-91 city directory as a physician with an office on Pinckney Street.

[3] Philip Langdon, Orange Roofs, Golden Arches (London: Michael Joseph Ltd.), 1986. 139-140

[4] Philip Langdon, Orange Roofs, Golden Arches. 141

[5] Jim Draeger and Mark Speltz, Fill ‘er Up: The Glory Days of Wisconsin Gas Stations (Madison, Wis: Wisconsin Historical Society Press), 2008. 47

[6] Quasi-mansard seems the most generous way to describe these roof treatments. Using faux mansard would connect them to their French origins, but sounds too high style. Fake, ersatz and counterfeit all seem too harsh.