From Privy to Bathroom

By Michael Bridgeman

James Mackin in 1922

When Mayor Albert Schmedeman presided at the opening of Madison’s Nine Springs sewage disposal plant in June of 1928, he also formally put James Mackin in charge of the new facility. In his first city job in 1897, Mackin supervised laying a sewer line as Madison prepared to open its first sewage treatment plant. He was named superintendent of the system in 1916, a job he held until his death at 66 in 1930. Mackin’s 33 years on the payroll saw big changes in Madison’s treatment of wastewater and its quality of life.

Click images to view full screen

Water In, Water Out

When Mackin started working for the city, flush toilets (or water closets) were still relatively rare in Madison. Indoor plumbing, uncommon as it was, used gravity to flush water through pipes, either from an attic cistern that collected rainwater or a water tank above the toilet. Many water closets flushed directly into the nearest lake, river, or creek, while others handled human waste in the same way as outhouses, sending it to privy vaults which had to be emptied two to three times a year, or cesspools which required even more frequent attention. Regardless, the discharge polluted surface water and groundwater and produced noxious odors.

Water closet from 1895

The well-to-do, like Timothy and Elizabeth Brown (116 E. Gorham St.), had more options than most Madisonians. They collaborated with three Mansion Hill neighbors to create a private sewer system that discharged waste into Lake Mendota. When the Park Hotel opened in 1871, it offered the first full indoor plumbing on the square; the discharge presumably went to Lake Monona. Therein lies a tale told in considerable detail by David Mollenhoff and Stuart Levitan in their accounts of Madison history (see sources below). The short story is that Madison began delivering clean water through a municipal system in 1884, which would eventually bring pressurized water into all buildings within the city. The second part of the problem—treating wastewater—didn’t begin in earnest until 1899.

Bringing the Privy Indoors

“From time immemorial, human waste was associated with the out-of-doors,” writes Merritt Ierly. “Using either a privy or, in more primitive times, a pit, one went outside to relieve oneself. If one used a chamber pot inside because of the weather or the hour of the day, one took it outside to dump at the earliest opportunity.” Simply having water piped into the house did not automatically mean people were ready or eager to bring their privy indoors. Privies like the one behind the O’Dea House on Park Street may have remained after they were no longer necessary.

O’Dea House with privy, before 1912

Mackin was on staff in 1899 when Madison’s first waste treatment plant went online. Built by a private operator, the facility failed and was quickly taken over by the city; a new septic system opened in 1901. A larger sewage treatment plant on Packers Avenue opened in 1917, shortly after Mackin was named superintendent of the sewage system. That same year saw considerable investment in sewer lines throughout the city.

Main façade of the Dudley House (demolished)

The combination of municipally supplied water and sewage treatment promised benefits to residents of all social classes, though on different timetables. According to Alison Hoagland, “Possession of bathroom fixtures was a factor of money and, as such, a bathroom helped to define class.” Plumbing and fixtures were expensive and they were often obtained one at time, even by the wealthy, and were frequently isolated from each other. By the end of the 19th century, however, most well-to-do households had the three-fixture bathrooms that quickly became standard.

Floor plans of the Dudley House as drawn in 1940

For existing houses, bringing the privy into the house meant finding a location. Two common solutions were adding a room or taking a room. The William Dudley House (508 N. Frances St., demolished) was recorded in 1940 by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). When Dudley built his Italianate-style house between 1852 and 1860 it may have had no indoor water closet. The small bath on the first floor at one end of the rear porch is adjacent to the kitchen and may represent an “adding a room” solution.

The second story was completed after the Civil War. The rooms labeled bath, closet, and alcove occupy a space equivalent to the bedroom across the hall and suggest “taking a room” to accommodate a larger, three-fixture bathroom. Regardless, the 1892 Sanborn fire insurance map shows no outbuildings on the Dudley property.

Wisconsin State Journal, Feb. 24, 1875

It's worth noting that in the 19th century Madison had commercial bathhouses, as did most cities and small towns of the period. Mrs. Doctress Wilson advertised her Turkish Bath in 1875. Prof. Gustav Winkler offered Turkish and Russian Baths beginning in 1886 at an establishment on East Mifflin Street.

Modern Times

Hoagland calls the introduction of the bathroom at the turn of the 20th century “probably the single greatest change to the architecture of middle- and working-class houses.” The proliferation of sanitary plumbing was driven by concerns over health, status and privacy and supported by city codes and aggressive investment in municipal infrastructure. Robert J. Gordon writes, “The nationwide percentage for private indoor toilets was between 10 percent and 20 percent until 1920, after which the percentage jumped to 50 percent by 1930 and 60 percent in 1940.” When the United States Census first asked about plumbing facilities in 1940 the data showed disparities in flush toilet distribution for different locations: 83.0 percent for urban housing, 43.2 percent for rural non-farm housing, and 11.2 percent for rural farms.

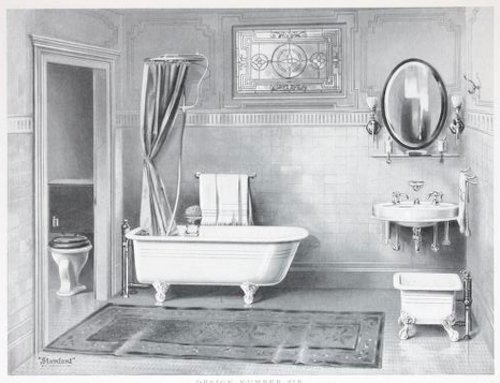

An unaltered bathroom is rare in older houses, but printed sources offer evidence of the evolution of this new domestic space. The Radford Company was a prolific publisher of house plans. One of their earliest publications in 1903 showed bathrooms in most (but not all) floor plans. The plan below let the builder use a second-floor space as “store room or bath room.” The illustration of the bathroom also dates to 1903. The toilet on the left is in a “closet,” an early arrangement that has reappeared in some 21st century houses.

In 1915, anticipating a new sewage plant that would go online in two years, Mackin said he expected no more trouble until 1950. “American homes are the leaders when it comes to ideal, up-to-date bathrooms,” declared an article in the State Journal (Oct. 1, 1913). By this time, that ideal usually meant a sink, tub, and toilet. Madison plumber William Schwoegler offered to install just such a bathroom “in your bungalow” for $48.

By the 1920s, the bathroom had become a well-integrated part of any modern home, like the design Madison architect Lewis Siberz entered in a competition for small houses conducted by the Chicago Tribune. Then a draftsman in Frank Riley’s office, Siberz devised a brick colonial design with the bathroom at the top of the stairs near the second-floor bedrooms.

The 1920s also saw the introduction of color fixtures as seen in a 1929 catalog from the Kohler Company. The copywriter fluttered: “Beauty of design and beauty of color go into this truly modern bathroom,” with fixtures that “have a grace of contour, a touch of daring, and an artistic splendor…”. With less lofty prose, local plumber W.J. Hyland promised to bring “Bathroom modernity” to your home. Though we can’t see color in his newspaper ad, we can see decorative tilework, a built-in tub (rather than a claw-foot), and a showerhead that projects directly from the wall rather than being suspended from a rickety ring.

A few months before James Mackin died of a heart attack in 1930, the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District was created to handle collection and treatment of sewage for Madison and surrounding communities. There have been eleven additions to the Nine Springs plant since then. Today’s home owner faces a dizzying array of bathroom plans, materials, fixtures, and finishes. Still, the notion of what constitutes a modern bathroom—a sink, a tub, and a toilet—hasn’t changed all that much in the little more than 100 years since the privy moved indoors.

Principal Sources

Hoagland, Alison K. “Introducing the Bathroom: Space and Change in Working-Class Houses” in Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. Vol. 18, No. 2 (Fall 2011). pp. 15-42

Gordon, Robert J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living After the Civil War. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. 2016. pp. 122-124 et al.

Ierley, Merritt. Open House: A Guided Tour of the American Home 1637-Present. Henry Holt and Company, New York, N.Y. 1999.

Levitan, Stuart D. Madison: The Illustrated Sesquicentennial History, Volume 1. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wis. 2006. p. 164-165 et al.

Mollenhoff, David V. Madison: A History of the Formative Years, Second Edition. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wis. 2003. Pp. 205-15, pp. 364-368.

Image Credits

James Mackin in 1922 — Wisconsin State Journal. May 15, 1922.

Timothy and Elizabeth Brown House — WHS Architecture & History Inventory #28948. 2005.

Early view of the Park Hotel — Unknown source. Undated.

Water closet from 1895 — Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

O’Dea House with privy — Wisconsin Historical Society, WHI-102427. Before 1912. Used by permission.

Dudley House drawings — Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, and William Dudley. Dudley House, 508 North Francis Street, Madison, Dane County, WI. Madison Wisconsin Dane County, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/wi0074/.

Plan published by the Radford Company — Building Technology Heritage Library. The Radford Architectural Company. 1903. urn:oclc:record:1051759599.

Illustration from the Standard Company — Building Technology Heritage Library. Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company. Modern Bathrooms and Appliances. 1903. ark:/13960/t3fx8936z.

1927 design for a five-room house by Lewis Siberz — Chicago Tribune Book of Homes. Chicago Tribune. 1927. p. 60.

Kohler Company catalog — “Modern Beauty and Usefulness in Plumbing Fixtures.” The Kohler Company. ark:/13960/t5hb0bs4n. 1929.

Modern outhouse — Photo by Michael Bridgeman.

Vintage outhouse — Photo by Michael Bridgeman.